No risk = No magic

post #0002

september 30, 2022

In the world of consumer technology, 2005 was perhaps the most transformative year for the smartphone. No, I do not have the dates wrong. I was working at Apple that year, and am well aware that the iPhone did not launch. In fact, we did not announce it to the world until two years later. Nor did Google have a presence in the industry. Their first Android phone was the HTC Dream which would not be announced until September 2008.

So what was so special about 2005? That year, RIM, the maker of the BlackBerry, ended its fiscal 2005 with 2.5 million subscribers and surpassed $1 billion in annual revenues for the first time in the company’s history. Palm, the once popular hand-held device maker, had lost market share that year, and also announced it was abandoning its in-house operating system to pursue a partnership with Microsoft. The world’s largest phone maker at the time, Nokia, had no smartphone in the market that year (nor would it for several more)!

The two companies whose names are now forever synonymous with, and responsible for, ushering in the smartphone era were not even present in the phone market that year. However, discreetly in the background, each had made what I would argue to be two of the most influential acquisitions in history, one made by each Apple and Google.

The former served as my own personal catalyst for becoming a lifelong M&A executive and believer in the innovation unlocked through acquisitions. Each deal provided their acquirer with core innovations that accelerated their company’s time to market, competitive differentiation, and some 17 years later are quite literally touched by every consumer in the world to this very day. I will return to these two acquisitions later in the post.

In the interim, I want to share some of my own insights into why taking these corporate risks, specifically through acquisitions, can provide outsized returns (aka “magic”) to most any other strategic alternative. Without mention, there is significant post-acquisition, integration and operational work that goes into making those investments successful, and that work will be discussed in countless, future posts.

For now, some of you have likely heard folks say that the biggest risk for a company is taking no risk at all. In highly competitive, quickly evolving industries such as consumer technology, this should make sense to even conservative investors of capital. When winning requires constant movement, stasis (or the lack of innovation) clearly loses. Do nothing, gain nothing. No risk, no magic.

If you read my last post, “THE only 2 questions,” then you know that there are four alternatives used for determining strategic pursuits, restating them for reference: 1) build something, 2) acquire things, 3) partner/ invest in stuff and 4) doing nothing. These alternatives each carry with them some level of inherent risk. In business terms, the output of these combined corporate risks is ultimately measured economically.

Notably, each alternative also has two fundamental inputs: frequency and cost. How often will we pursue such a strategy? And, how much will it cost us to pursue (e.g. resources, time, capital, etc)? Such inputs are entirely within the control of the company pursuing them. In other words, they are known, and quantifiable with some degree of certainty at the time that the company decides to pursue their given strategy.

For simplicity, and since no company exists alone in a market, let’s compare two companies to illustrate how a one-time game of risk might look. The table below shows Company A (the column) vs Company B (the row), and the output illustrates an expected economic or competitive outcome.

Company A vs Company B - One time game, strategic chessboard

Note that the only strategy guaranteed for Company A to “Win” is when Company B does nothing, and conversely, Company A is guaranteed to “Lose” when it pursues doing nothing. In all fairness, this is highly contrived, unlikely scenario and assumes lots of other variables are equal or held constant. But I think you get the point. All else held equal, motion outperforms stasis.

Do nothing, gain nothing. No risk, no magic. Or worse, you will lose something (or everything). Do something, and well, it depends. Truth be told, over time, a sophisticated company will typically pursue some combination of each alternative. Operating within a truly competitive market ends up feeling at times like playing four-dimensional chess. Can make your head hurt, but I love it!

Today, I want to try and simplify the game theory to just two types of company strategies:

those companies that pursue innovation via acquisitions; versus,

those that focus on maintaining status quo or incremental product enhancements

The former could be categorized as having greater risk than the latter. However, I want to demonstrate in the ensuing paragraphs that risk is actually limited for #1 and what appears to be a risk-free or at least more risk-adverse strategy for #2, could end up with sometimes catastrophic and irreversible economic consequences.

Let’s return to the two acquisitions that I alluded to in the opening. These were small deals, relatively speaking. While specifics were not announced, one can assume they were therefore not material to the company’s respective economic sizes at the time. Apple purchased a company called FingerWorks, whose core IP & technology were focused on multitouch and the foundations of the iPhone experience. Google acquired Android that same summer. While Apple had a few years of portable hardware development with the iPod, and Google had become a public company with proven internet prowess, neither had broken into the mobile phone market in a big way.

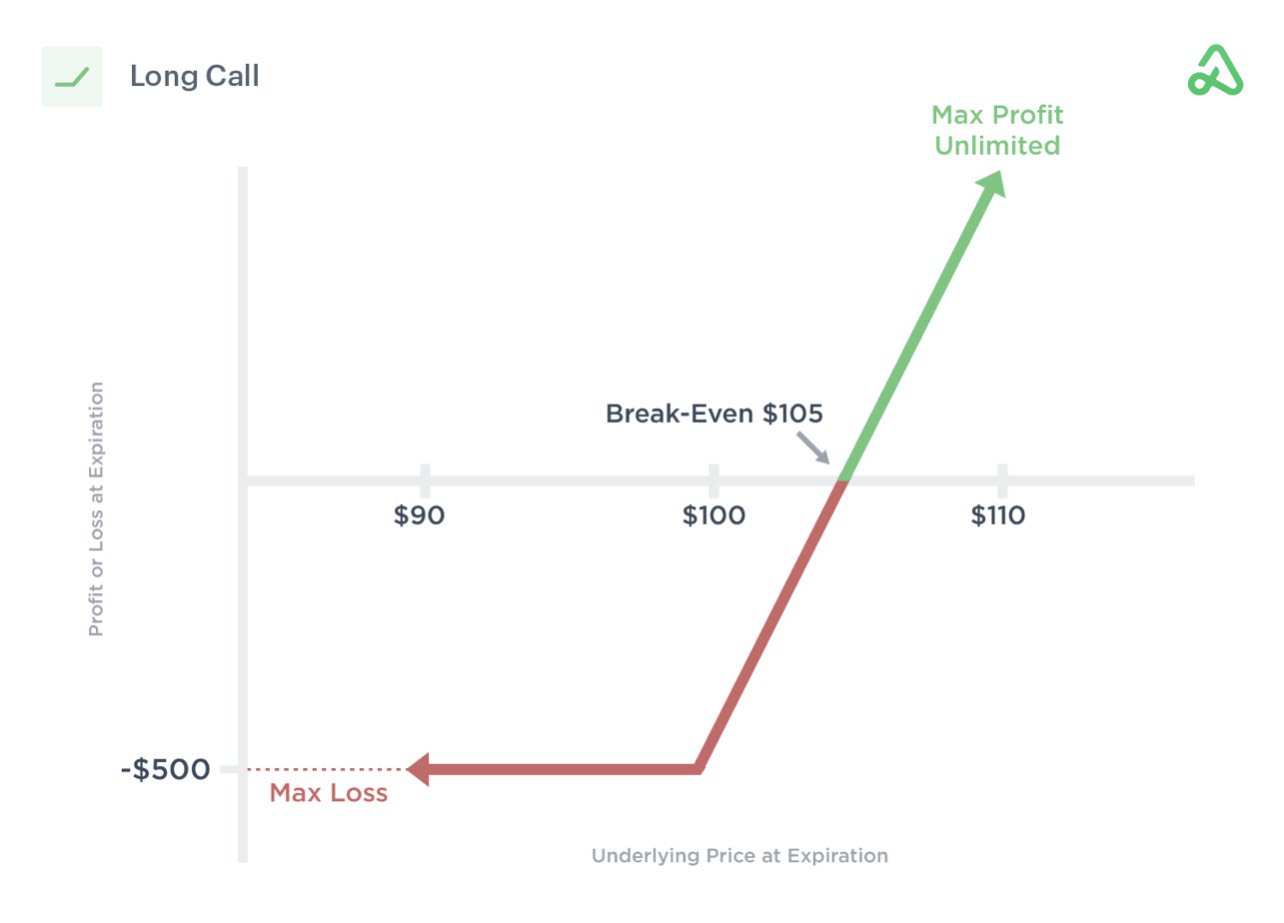

While each of these acquisitions were relatively small, the innovation and markets they unlocked have been now proven to be exponentially larger and more valuable than the risk taken by the acquiring companies and founders at the time. To help illustrate this paradox of return-on-risk, I often think of call options. In other words, if you were to assume that the investment for purchasing a call option is the risk, there is limited downside; you lose the cost of purchasing the call itself. However, the upside, should the stock or asset perform is uncapped, it is unlimited upside.

Using the call option example for a moment... To use round numbers, assuming Google spent around $50M on acquiring Android and it turned out to be a failure, it would have cost them $50M plus any additional expenses associated with integrating the team, technology and other related research and development, marketing and other costs. Conversely, as it turned out, Android has been a tremendous success, and as of 2016, Android had reportedly generated over $22 billion in profits and been installed on over 80% of the world’s smartphones (data source per Oracle court filings at the time). This is not to mention the countless other forms of market innovation and financial returns this deal brought Google/ Alphabet.

Similar statistics hold true for Apple’s bet on multitouch and the impact that its FingerWorks acquisition had on the company’s iPhone growth. In Q4 of 2016, to compare with Android, Apple had shipped over 45 million iPhones which generated the company over $28 billion in revenue (data source Apple 2016 filings). Again, this is not to mention the countless other forms of market innovation and financial returns that this deal brought Apple, such as the iPad.

Of course, I am greatly oversimplifying how much other hard work, operational excellence, built-in capabilities and re-investment went into those product lines. However, one thing is rooted in both: without making these investments and taking on these, neither Google nor Apple would have innovated in the same way. It also benefited them as acquirers that they were in a competitive market with others who chose sub-optimal corporate strategies.

So, what happened to the other “no risk” taking companies, or at least those that were more reluctant to adopt motion in the smartphone evolution… Let’s go back and see how companies like RIM/BlackBerry and Palm faired during the same time period.

First, I wanted to point out that every public company has legal teams that publish their risk factors, seen or unforeseen, in case their operational performance does not yield the anticipated market outcomes. At the time, both aforementioned companies were public. I went back through RIM’s 2005 Annual Report and have included some of their risk factors here for reference:

These look very similar, almost boiler-plate, for every public technology company to this day, with some minor edits around the edges. However, these risks were so important, that RIM actually includes them twice in the same filing!

Switching over to the expected outcomes from risk-investing, what is the amount of winning, or “magic” a company might generate dependent upon? Referencing RIM’s risk factors section, the two that can accelerate such innovation or “magic” is the company’s “ability to enhance current products and develop and introduce new products,” and the company’s ability to out-innovate the “competition.”

Regarding the former risk, RIM definitely did not introduce new products to an evolving market fast enough, or launch products that were innovative enough to deter others’ growth. And, we know what Apple and Google were able to accomplish as that competition, even though RIM likely did not think of them as such at the time. Here is a chart of RIM’s market share within the smartphone segment from 2007 - 2016. I think this says enough about what I mean by no-risk, no magic:

While it took some time for the competition to catch up, this was likely due to the fact that BlackBerry held a stronger moat within the enterprise segment made possible by innovations that were ultimately surmounted in 2010/2011 by both iOS and Android. As such, by the same period in 2016 in which Apple shipped 45 million iPhones and Android was installed on over 80% of all smartphones, RIM / BlackBerry had only shipped approximately 200 thousand devices and had less than 0.1% of the smartphone market.

Palm had faced an even earlier and more turbulent demise, too interesting to go into during this post. However, the company was acquired by HP in 2010 for $1.2 billion and ended production of Palm and its webOS related devices just one year later in 2011.

In short, going back to our strategic chessboard, Apple and Google utilized key acquisitions to bolster their strategy and thus defeated Palm (partner/license) and RIM (build) who were more reticent to take on alternatives that were necessary in an evolving consumer landscape during pivotal industry transformation.

While this case study may seem extreme, there are countless like this across industries. In the consumer technology industry, motion defeats stasis, time and again. That motion often entails risk (sometimes perceived to be greater than it is), and knowing how to manage, limit and appropriately re-invest in areas to unlock potentially limitless economic returns is the magic that separates market winners from losers.

In order to begin to unpack how to mitigate risk post-acquisition, I am going to introduce a risk-reduction framework that I call “AIR” in my next post. This will help both buyers and sellers in best determining their ability to generate long-term value together both before and after an acquisition takes place.

If you are thinking about pursuing an acquisition, in the midst of one, or simply want to learn more by diving a bit deeper or getting more tactical with any of this, you can always reach out to me gary@kokua.ventures